If you’ve ever picked up an illustrated book written by J.R.R. Tolkien, or spent time clicking around on the internet in fantasy circles, or if you’d seen the posters on my dorm room wall years ago—or, heck, scrolled through any of the posts of The Silmarillion Primer—basically, if you’ve lived on Planet Earth over the last few decades, then you’ve surely chanced across the scenic, brilliant, and exceedingly prismatic illustrations of Ted Nasmith. I mean… if chance you call it.

Ted is a luminary, an artist and illustrator of… well, many things, but he’s best known for depicting Tolkien’s world more or less how we’re all imagining it. Or maybe you’re imagining it, in part, due to Ted’s work. From official Tolkien calendars to illustrated editions of the professor’s books to The Tolkien Society’s journal covers, he’s dipped his toe and his brushes into Tolkien’s mythology so many times there’s just no keeping track of it all. You know, I’m going to come right out and say it: Ted Nasmith is basically the Bob Ross of Middle-earth.

…Well, minus the almighty Bob Ross hair, but definitely including the soft-spoken manner and sage, genial warmth and overall friendliness. Somehow Nasmith makes what is insanely challenging look easy, and when you look at his paintings—especially his landscapes—you’re sucked right into that world. It’s not his world, per se, but it’s one to which you get the sense Tolkien would give his stamp of approval. These essentially are scenes in Arda (a.k.a. the whole world that includes the continent of Middle-earth).

Now, we know that Amazon has some mysterious wheels turning over its upcoming Lord of the Rings-related series, but wouldn’t it be great if we also got a show called The Joy of Painting Middle-earth wherein Ted Nasmith walks us through creating and inhabiting the realms and spaces of Tolkien’s legendarium? Can we get that please?

Happy little Ents…?

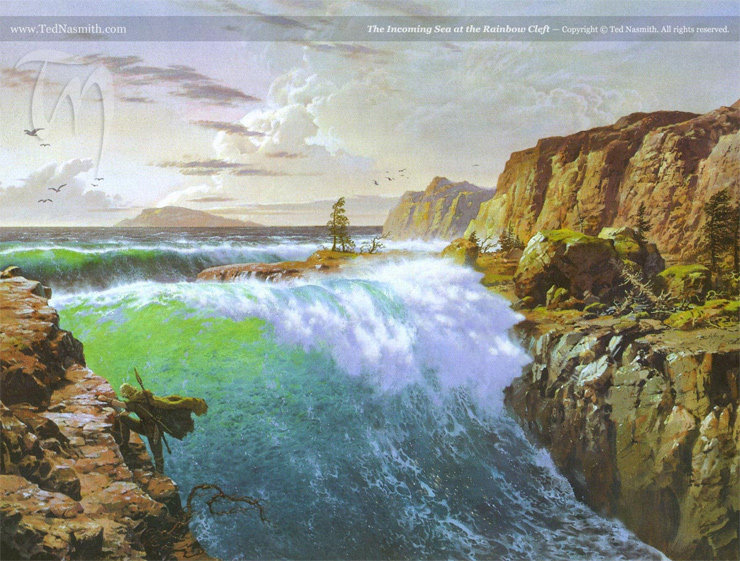

All right, so it’s wishful thinking. See, the story goes like this. I emailed Ted Nasmith quite a few times while I was working on the Silmarillion Primer and he gave me permission to include as many of his works as I wanted. I appreciated that enormously for obvious reasons, but it also turns out he’s a super nice guy. He even helped me understand his approach to the geography of Cirith Ninniach, the Rainbow Cleft—that rocky, water-filled pass in the Echoing Mountains of northwest Beleriand.

Which was perfect accompaniment to my treatment of the chapter “Of Tuor and the Fall of Gondolin.” (An an aside, Ted also contributes to my growing conviction that Canadians are just better people, overall. Yeah, I’m also talking about you, Rush, Ed Greenwood, John Candy, et al.)

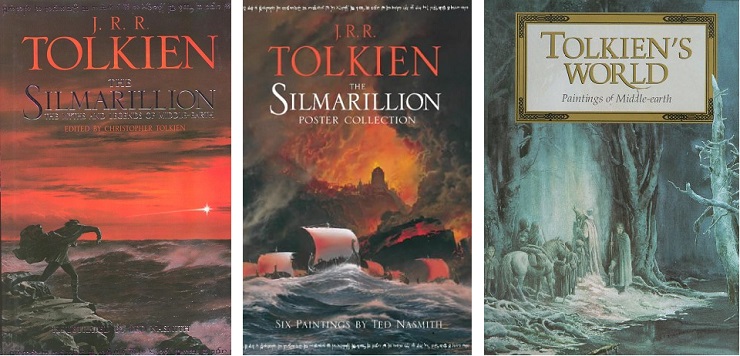

The bottom line is that his paintings have been influential in the imaginations of many, many people, even (or especially) other Tolkien artists I’ve corresponded with. From the the illustrated Silmarillion, to painting anthologies, to a whole slew of calendars and even card games, you can’t look any which way and not see Ted’s vision of Middle-earth sprawling out before you. And this, of course, started long before the Jackson films. He’s part of—in my mind, and I think many others’ minds—the Tolkien Triumvirate of artists, alongside Alan Lee and John Howe.

Now, I’m a longtime fan, and here he was, both friendly and responsive…so it was time to do something about it. I decided to throw some interview questions Ted’s way. And he was kind enough to oblige me. So here’s how that went…

Ted, can you tell me, in a nutshell, how you discovered Tolkien and made his work a big part of your career?

Ted: The capsule answer is that at the age of 14, my sister suggested I might like The Fellowship of the Ring, and that was it. I was enchanted from the moment I began reading, as though I’d found something I had no idea I was searching for.

That’s a sentiment a lot of people have, truly. While some don’t really sink into the world until they’ve made a few attempts, some are drawn in on the very first helping.

Can you remember what might have been the first sketches or doodles you made—like, just for fun—relating to The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings?

Ted: I can. I saved most of the early drawings, which explored various characters and random scenes, and out of which I began to more carefully build my sense of how I wanted to express my new artistic passion.

Any specifics you can name?

Ted: I drew things like my early impression of Gandalf, a Dwarf, a spewing Mount Doom, and a small portrait of Samwise. The latter seemed to well capture his quiet personality, and became the template from then on for images of him.

You seem to work mainly with gouache paints. What is it about that, as opposed to traditional oil paints, or watercolor, etc., that works for you? Or for Arda in general?

Ted: It’s purely a personal preference that stems from its use as a common illustrators’ medium. It dries quickly, but can be wetted and re-worked. It’s both opaque (i.e. covers well) or translucent depending on formulation. It can be rendered such that it resembles oil paintings or watercolour alike, but without the technical drawbacks of oils. Besides being common among commercial artists, it was also common for architectural renderings, partly for its excellence for fine detail, and partly because one is always prepared to paint over areas that require amending as the process of architectural design evolves for each project.

Practicality! So what do you think about the digital painting all the whippersnappers are into now?

Ted: I admire much of what I’ve seen in digital painting and drawing, and understand its importance as a new medium with limitless potential, but like synthesized sounds in music, it is telling that it seeks to imitate established art-styles and looks. That’s a practical issue, since it means its traditional-looking artwork can also be transmitted over the internet, and has a life of its own in the cyber realm. But it is not recognized as much as an art form unto itself, though I’ve no doubt there are people nowadays exploring pure digital art concepts that little resemble traditional forms.

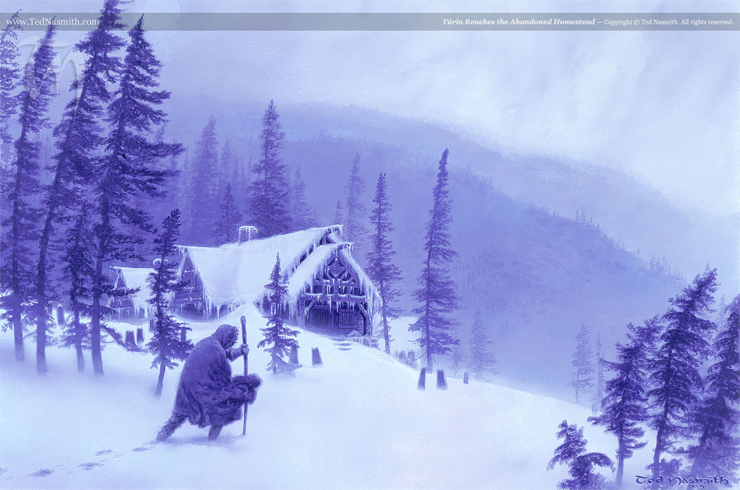

A lot of artists depict moments or specific scenes from the books—and you’ve certainly done many yourself—but it strikes me that you primarily paint places. Sites, locales, regions. Something about the way you portray them makes them look timeless; I can well imagine those same sites both before and after the famous events they’re associated with. For example, “The Glittering Caves of Aglarond” or the house in “Túrin Reaches the Abandoned Homestead.”

Somehow you’ve made it easy to picture the Húrin family home in happier (and all-too-brief) times, of a much younger Túrin running across that countryside with his baby sister, Lalaith, when it isn’t a brutal winter. How do you do that?!

Ted: Yes, it’s always been Tolkien’s geography that I’ve been drawn to in particular, with the scenes of characters in situations a close second. I do tend to think ‘in the round’ while composing a scene, or designing what I think the dwelling might look like (in the case of the Túrin scene you cited) in such a way that if I end up setting other paintings there, I have a ‘set’ figured out, as though it was for a movie shoot. I also, not uncommonly, think about the elements of a painting for months to years before beginning to draw thumbnails.

That’s some forward thinking. So then I’m betting you’ve got some places “mapped” in your head already that you haven’t even started painting yet. Also, you’ve rendered various versions of the same character, scene, or location—from different angles and sometimes with different styles. Galadriel comes to mind, as does Gandalf’s escape from Isengard, Frodo at the Ford, or the valley of Rivendell itself.

Is it just different commissions bringing you back to these places out of necessity, or is there something that brings you back by choice?

Ted: A bit of both, actually. If a new commission requires me to depict a locale I’ve covered previously, it’s an opportunity to flesh it out with a newer understanding of it if I wasn’t entirely satisfied with the first go-round. That was the case with “Gwaihir the Windlord Bears Gandalf from Isengard.”

For Rivendell, it has been a case of returning to it both because some commissions were a chance to re-interpret it with variations on previous versions (e.g. the Danbury Mint collectible plate) as well as because I have been inspired by discovering an artist like Andreas Achenbach, or because (latterly) I’ve visited the Swiss valley that was Tolkien’s original inspiration.

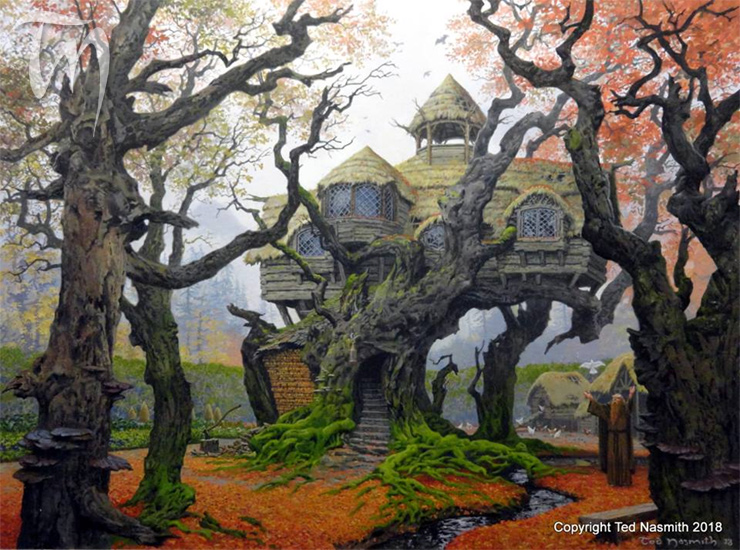

Another prime example is Rhosgobel, near the borders of Mirkwood, which you’d only recently shared on Facebook—after having initially painted Radagast’s house for a collectible card game back in the ’90s, now you’ve revisited it with full autumn splendor. And not a rake in sight.

Can you tell me anything about these private commissions? Are they works that fans have their hearts set on seeing depicted?

Ted: Yes, exactly. They already appreciate my established Tolkien art, and are seeking a painting of a scene of their choosing. My agent and I work with them to establish how I can deliver their choice of subject, and usually they trust in my judgment as to how I will achieve that, and because I send jpgs as the work evolves, they are encouraged to participate in the creative process, via my agent.

You’ve said elsewhere that it would have been nice to been able to pick Tolkien’s brain concerning his world, to better understand and depict it. If there was one whole region of Tolkien’s world that he didn’t detail much but you wish he had so you could try exploring it in art, what region would you choose? Perhaps Far Harad, the Enchanted Isles, or the Dark Land (that continent south-east of Middle-earth), for example. And why?

Ted: The more I understand about Tolkien’s creative process for inventing Middle-earth, the more I realize that he gradually built it up somewhat piecemeal as he continued writing about it. For me, the area I’d have wished for more information on would be Valinor and its lands, and maybe areas of Beleriand that are still sketchy. That said, one of the features of both The Hobbit and The Silmarillion that I love is its relative simplicity around place descriptions. Why? This allows me greater freedom to interpret.

In contrast, I once was nearly obsessively concerned with what Tolkien ‘would have approved,’ but over the years I’ve realized that as long as I trust in my instincts and love of his work, there is room for much variation in interpretation of even detailed descriptions. Which is a reason to love many other artists’ versions of the scenes, too. Some of that art, however, is too idiosyncratic and off-centre to be considered seriously!

Solid answer, sir. And I can kind of relate. There’s no way the Tolkien would have been okay with my Silmarillion Primer’s execution, or all its jokes. But I trust that, in the very least, he would eventually have understood the intent, and the fact that it’s love for the work that brought me to it. And maybe, just maybe, it will help others give that book a chance.

Anyway, on a related hypothetical, if you could receive an exclusive, never-before-seen-but-fully-written description (from Tolkien) of one specific site in all of Arda, what place would you choose? For example, Angband, Barad Eithel (the fortress of Fingolfin in Hithlum), Himring (the fortress of Maedhros), or the Stone of Erech (where the oathbreakers first swore their oath to Isildur).

Ted: Tough one, but I’ll go for Alqualondë. The ones you cite are good possibilities, too; indeed the Elf-realms overall would be great to know in more depth; Nargothrond, Menegroth, Angband, Gondolin, and others. I could extend this to Númenor, too, quite happily.

Haven of the Swans for the win! For those of you who haven’t read The Silmarillion at home, Alqualondë is the city on the edge of Aman where Eärwen (Galadriel’s mom) came from. It’s also where Elwing (wife of Eärendil the Mariner) reconnected with her ancestral kin. Oh yeah, and the site of that first tragic Kinslaying.

As a reader, especially one who loves the History of Middle-earth books nearly as much as Tolkien’s chief works, I especially enjoy illustrations of scenes that are implied in the narrative but are never actually depicted within the text. And you’ve made some like this, such as “The Blue Wizards Journeying East,” “Thrain discovers the Lonely Mountain,” and “Fire on Weathertop.” In the latter, we see Gandalf fighting his way free of the Nazgûl—whereas in the book, Gandalf only briefly mentions this encounter.

Yeah, I love these. What would be another moment or two like this that you’d love to see yourself?

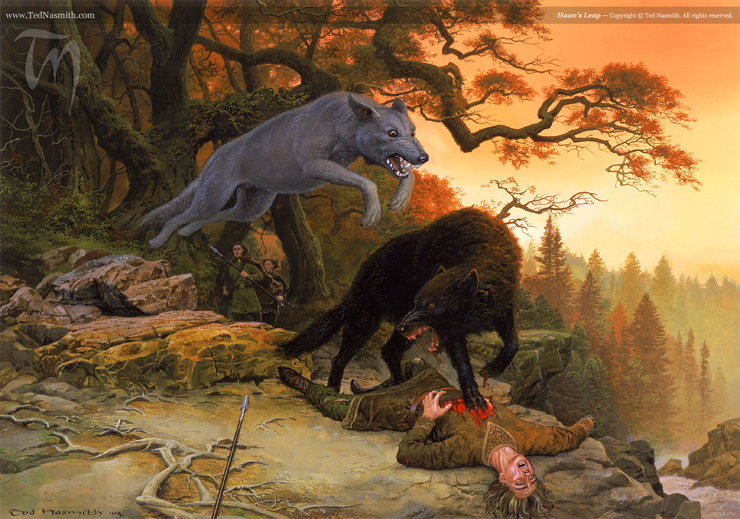

Ted: Big question! There are many such scenes I’d enjoy conceiving of. Currently I’m accepting private commissions of Tolkien subjects, and one, Turgon at Fingolfin’s Cairn, was of this kind. That is, suggested to me, opening the door to a fairly obscure scene. There are both unspoken scenes as well as obscure, minor ones, and I suppose an example of the former that I’d love to do, would be Beren and Lúthien as they grew in their love while alone together in Neldoreth.

We spend most of our time reading about the heroes under duress. It’s always nice to see them resting, or spending time with one another. So yeah, some glimpse of Beren and Lúthien’s time together would be great. Pre-Silmaril, pre-Wolf. Pre-Thingol, for that matter.

So who, beyond Tolkien, are your literary or artistic heroes?

Ted: I have enjoyed George R.R. Martin’s Ice and Fire saga very much, and I’ve illustrated a deluxe edition of A Game of Thrones, as well as contributing substantially to The World of Ice and Fire. Also the 2011 Ice and Fire Calendar. I’m a big admirer of George MacDonald’s fairy stories, and though it’s been years, I once read everything I could find of Joan D. Vinge, all of the novels by Frank Herbert, and most of Michael Bishop’s novels. I read eclectically, however, thrillers, mysteries, books I come across in reviews, as well as a diverse choice of non-fiction scholars, testimonials, biographies, and expert pundits on a range of subjects.

Diverse indeed, as you can’t get as distinct from Martin as MacDonald! Except, of course, that both are/were talented writers.

And now that you’ve namedropped George MacDonald, I’ll just say: if I had a million bucks, I’d commission you to illustrate his book Phantastes thoroughly. That would be perfect. For one, it’s not such a far cry from Middle-earth, after all, being suffused with fairies and forests and religious sentiments. It’s obvious the beauty of the natural real world inspires you—just as it did Tolkien. What’s your most real-world visitation that inspired you?

Ted: That one’s easy: Switzerland. In particular, places Tolkien is likely to have passed through in 1911 during his trek with a large group, led by his aunt, a geography scholar (among the first female ones in Britain). I travelled there with my partner in the fall of 2017, and again last year, visiting several scenic places which inspired Tolkien’s Middle-earth landscapes. Northern Ontario, as well as the British Isles, have also long provided inspiration.

Okay, hear me out on this one. If they made a Middle-earth Theme Park and miraculously got The Tolkien Estate’s blessing (crazy, right?), then employed you for its concept art, what ride would you be excited to help design? For example… the Eagle Aeries of the Crissaegrim (a Matterhorn-style ride?), the Mines of Moria Runaway Mining Cart, or the Paths of the Dead (Middle-earth’s answer to the Haunted Mansion?).

Ted: I suppose—and I’m suspending my loathing of Peter Jackson’s “thrill ride” sequences in The Hobbit here—that a ride which took the rider through Lórien, then on down the Anduin’s rapids past the Argonath, ending at Parth Galen and an Orc attack, would be cool. (That said, I really don’t think the world needs a Tolkien theme park!)

Oh, it doesn’t. But yes, the barrel-battle and dwarf-and-dragon chase scenes in The Hobbit films are a low point. And I say that as someone who generally likes those films for what they are.

Is there any place in Tolkien’s legendarium you wouldn’t particularly want to take a stab at? Somewhere way too challenging?

Ted: It would depend. I’m not especially inspired by the battle scenes, and if I had to tackle, say, the Battle of Helm’s Deep, I’d work out a depiction which captured the event that isn’t excessively demanding. In instances of battle scenes I have painted, it’s a specific moment being rendered (e.g. “Fingon and Gothmog”; “Túrin Bears Gwindor to Safety”; “The Shadow of Sauron”; “Éowyn and the Lord of the Nazgûl”). There are places on the fringes of Middle-earth that I’d be open to as settings for a scene, but that otherwise aren’t especially interesting. It’s normal that in the rich source of ideas Tolkien’s ‘universe’ offers, most illustrators of it are attracted to imagery which has especially enchanted them, personally, and I’m no different. I’m equipped to illustrate nearly any place or scene in Tolkien, no matter if it’s especially interesting, personally. In any such instance, I instead focus on the craft of picture making, and get my reward from creating high quality art, no matter my personal preferences.

I’d say you can—though now that has me wondering if illustrating the legendary grinding ice of the Helcaraxë was interesting for you or not. Either way, it’s glorious, because somehow you’ve made it look both inviting and brutal.

Is there any surreal or funny story you can tell me about what it’s like being such a professional and widely known Tolkien artist?

Ted: I was once invited to Sao Paulo, Brazil as a Guest of a city university. My son was invited to come along, too, an avid soccer fan. We arrived at the airport on the day of our flight—paid for by my sponsor—only to discover that visas are required for travel to Brazil! The person who arranged my air travel hadn’t thought to check this detail, and I had no idea either. Panicky phone calls were made, explanations given, and my son and I headed to the Brazilian Consulate (thankfully it is in downtown Toronto) to apply. Normally, it’s a minimum ten days processing period, but under the circumstances, that wasn’t going to work. Very fortunately, an acquaintance and fan of mine, and who I was scheduled to meet with there, pulled some strings and got the visas issued within 24 hours, enabling us to board a flight the following day. We arrived in Sao Paulo, and were whisked through security (normally a potentially longer process of checks), then driven to the university campus immediately. This was the last day of classes for the semester, and I needed to give my talk that morning, whereas the original plan was to give me a day of rest prior.

So, after welcoming ceremonies (including some welcome coffee!) and a short speech by the clearly proud founder of the university, we proceeded to the lecture hall, and I gave a slide show to an appreciative group of students—with live translation by my friend, author Rosana Rios. Later in that very memorable trip, my son and I were indeed taken to a city stadium and watched a pro soccer game. We also flew up to Brasilia, and amid a rock-star treatment by local organizers and media, I also met my friend Ives, who works in the justice ministry, and who influenced the issuing of our visas. A wonderful gentleman, he showed us around Brasilia, a city I’d long found fascinating for its youthful architecture by Oscar Niemeyer. A couple of years later I provided illustrations to a scholarly book he wrote (only available in Portuguese: Etica e Ficcao de Aristoteles a Tolkien by Ives Gandra Martins Filho. It’s a comparison of Tolkienian and Aristotlian philosophies.)

That’s great. And actually, given Brazil’s many geological wonders, it’s no surprise to think you’d have fans there. We all know Tolkien’s own imagination was vast, but I wonder how Middle-earth might have sounded if he’d personally been there and seen some of it? Heck, Iguazú Falls could already be a place in the Vale of Sirion…

All right, time for some easy lightning round questions. So who is…

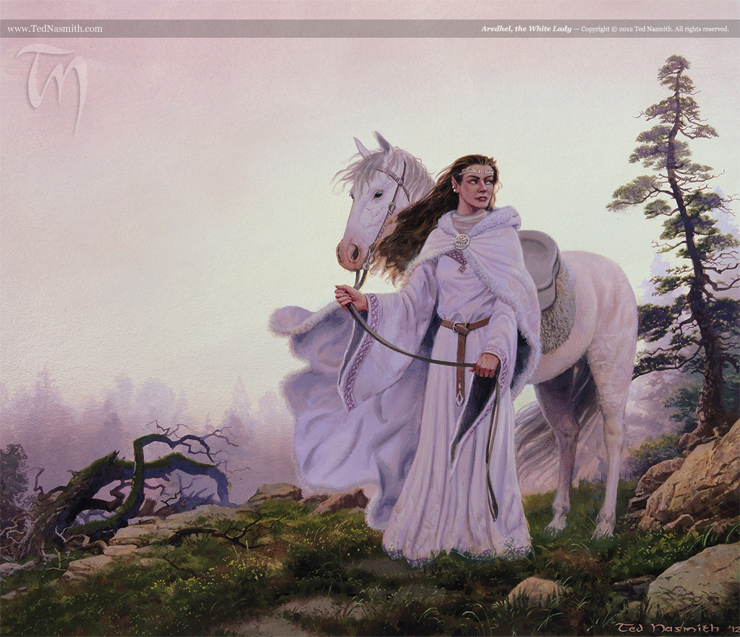

Your favorite Elf of the First Age?

Ted: Aredhel, I suppose. She has wonderfully human wanderlust, raising questions about how Elves cope with the inevitable boredom of living immortal lives.

Your favorite mortal man or woman of the First or Second Age?

Ted: I would say Túrin, far and away. He’s probably the greatest character in all of Tolkien; certainly among the cast of characters populating The Silmarillion.

Favorite monster of Morgoth?

Ted: Morgoth’s guardian wolf Carcharoth rates highest for me. (There’s also Ungoliant—but she’d scoff at being called Morgoth’s anything. “Fools—he be my bitch—not the other way around!”)

Ah, the dreaded Wolf and Shelob’s dear old mom! Good choices. But I don’t think Ungoliant would scoff so much as devour someone who says this in her presence.

Which of the Valar do you wish Tolkien had told us more about?

Ted: Nienna, Goddess of Sorrows.

Gandalf’s mentor, totally. He served a few of the Valar, but it feels like Nienna was his greatest influence. What’s a day in the life of Nienna like, I wonder.

So what are you working on now?

Ted: My current project is a private commission. It’s a depiction of the dawn approach to Edoras on horseback of Gandalf, Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli.

A Riddermark landscape that includes the White Rider and the Three Hunters? Isn’t there a limit to how much awesome you’re allowed to pack into one painting? I guess not.

Well, that’s that! A post-devouring-the-light-of-the-Trees Ungoliant-sized thank you to Ted, for giving me his time, and for humoring me over my silly questions, and for bringing all of us so much closer to Tolkien’s world via gouache and his lifelong passion for the art.

One final word, everyone else out there: If and when bibliophiles, executive producers, and industry nerds all get their act together and they finally brainstorm a Netflix original series called Of Beleriand and Its Realms, I want Ted Nasmith to be the official concept artist, if not an all-out showrunner. Can we at least all agree on this? (Bob Ross only had thirty-one seasons with his show. I’m just sayin’.)

This month, we’re celebrating the legacy of J.R.R. Tolkien with a look back at some of our favorite articles and essays about Middle-earth. A version of this article was originally published in January 2019.

Jeff LaSala, who’s personally responsible for The Silmarillion Primer, still has Ted Nasmith’s old calendar art cut up and tacked to the walls around his workplace. Tolkien geekdom aside, Jeff wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books. He sometimes flits about on Twitter.